There’s a scene in Roman Polanski’s 1976 film The Tenant where Polanski himself, starring as Trelkovsky, the meek and somewhat hapless new resident of an apartment whose previous occupant is in the hospital having thrown herself out of one of its windows, is discussing identity and personhood with Isabelle Adjani’s Stella. He philosophizes how, if parts of his body were removed, a tooth, an arm, his liver, he could refer to them as “me and my tooth, me and my arm.” But how far along would these amputations have to proceed before that statement because untenable. He asks, “if you cut off my head, what would I say… ‘Me and my head, or me and my body’? What right has my head to call itself me?”

I’ve been thinking about this idea in terms of band identity of late. Late last year I wrote a piece examining, among other things, whether the band Trooper, touring with no original members, could still be called Trooper. This question comes up again with the announcement that Black Flag will be one of the headliners playing at a local festival here in Fredericton this summer.

Since their formation in 1976, Black Flag has featured an estimated 26 members, the only consistent being Greg Ginn, guitarist and principle songwriter. That element puts the band in a very peculiar position. Most of the time the identity of a band is placed upon the singer / frontperson… though that’s largely because they are usually also the chief lyricists, but when they aren’t the waters can get a little murkier. This is an especially complicating factor with Black Flag as their featured lead singer for roughly half of their first decade was Henry Rollins.

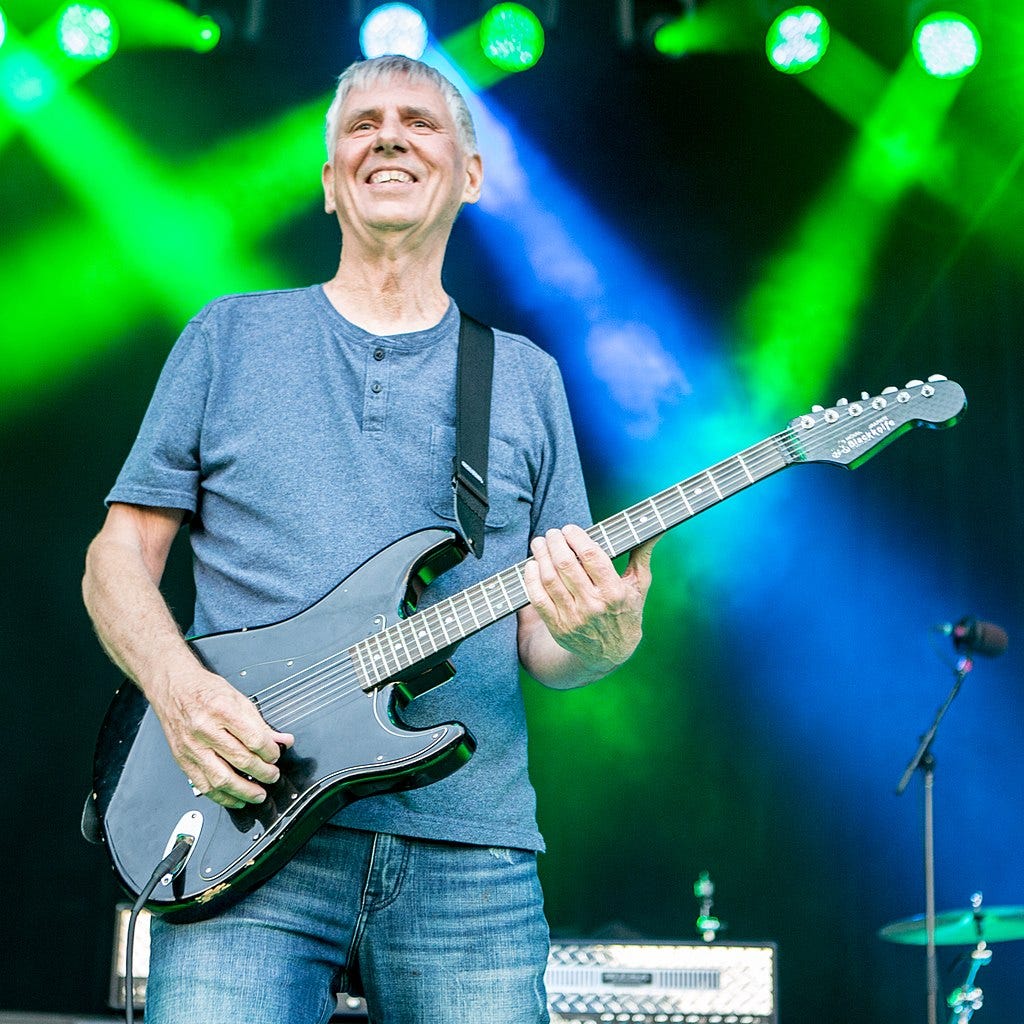

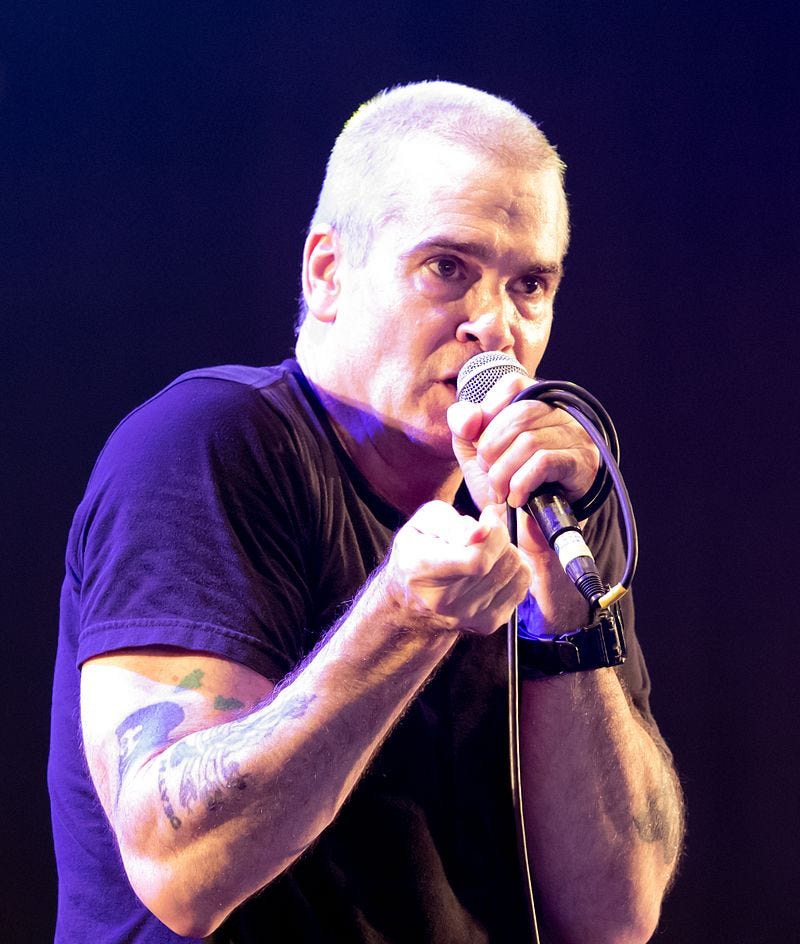

Though Rollins was the fourth person to step up to the microphone for the band, he was the lead through virtually all of their recorded output starting with 1981’s Damaged. Since the band’s initial break up in 1986, public awareness of Rollins only increased as he pursued projects as a singer, writer, and actor. Consider the above image of Greg Ginn and the one below of Henry Rollins. I’m the first to admit, having never really been a Black Flag guy, that I’d be unlikely to recognize Ginn on the street whereas Rollins is certifiably a “public figure.” Even Ginn must’ve felt this pressure to some degree, as Rollins tells it in his Black Flag memoir, Get in the Van, the band’s break up came via a phone call from Ginn. "He told me he was quitting the band. I thought that was strange considering it was his band and all. So in one short phone call, it was all over."

Since 1986 there’ve been the predictable periodic eruptions of activity from Black Flag. Brief reunion tours with mish mashes of new and legacy members. Notoriously there was a clash between Ginn and other previous Black Flag members Keith Morris and Chuck Dukowski when, in 2013, there were briefly two different line ups of the band playing at the same time. Morris and Dukowski had done a festival spot in 2011 playing pre-Rollins material from the early Nervous Breakdown EP that featured Morris on vocals. Their decision to expand this to an actual tour under the name “Flag” was not met with joy by Ginn.

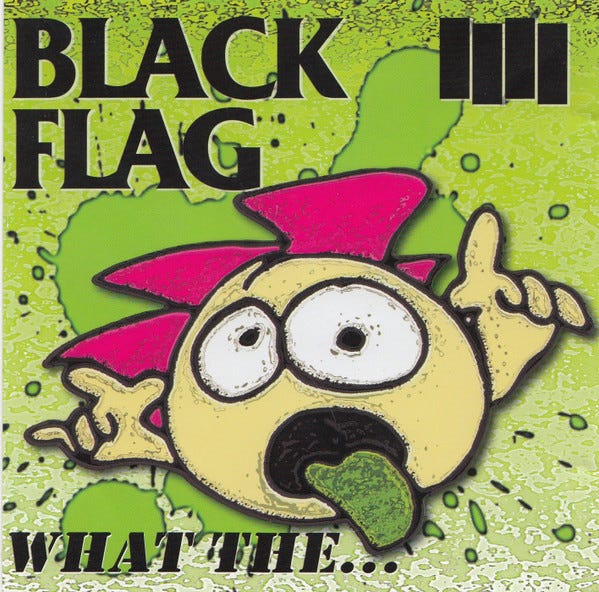

Since 2013 Ginn’s version of Black Flag has been fronted by Mike Vallely, a professional skateboarder and musician, making him the second longest consistent member of the band, though one who has not appeared on any recorded material. The only post 80s Black Flag music to emerge was a 2013 record on SST Records, the label Ginn owns and manages, called What the…, featuring the return of early member / singer Ron Reyes.

The Pitchfork review of the album cited it “much of the musical material is rickety. Too many songs here feel like aggregations of quirky, tossed-off riffs. Tracks like "I'm Sick", "This Is Hell," and "Wallow in Despair" are at once so busy and so inert—borderline nauseating in their repetitiveness and indistinguishability.” Most of the press surrounding the album came from an incident when, on a tour date in Australia just days ahead of the release, Mike Vallely, who had been acting as the band’s tour manager essentially performed a kind of hostile takeover, replacing Ron Reyes onstage during the show and ending Reyes employment by the band.

So the question remains, what parts of a band can be amputated and allow the remainders to identify as the band? There’ve been other examples from the simple to the ridiculous. Pink Floyd’s break-up / non-break up in 1986 as Roger Waters left the band expecting it to disappear. It didn’t. Yes has had so many members of the years that at one point in 2017 there were two versions of the band touring simultaneously, apparently without much in the way of disagreement. The Grateful Dead has continued to tour for coming up on three decades after the death of founding member, Jerry Garcia, most recently as Dead & Company that is a combination of original members and more recent additions.

The Dead is maybe an an example to consider when it comes to what makes a band. There’s been much talk about the culture of fandom that surrounds the band, so that the music and message, regardless of the source and/or argued authenticity, still carries on through time. Or maybe it’s something closer to something like sports fandom. Some people are lifelong supporters of certain teams despite that over a ten or twenty year span that team’s membership is completely different.

So maybe, like so many others, Black Flag have become a punk rock “Home Team” that fans can cheer for, regardless of line up changes? A kind of band-slash-brand loyalty that survives through t-shirts, graffiti tags, and tattoos? Nothing wrong with that as far as I can see.